This is an encore of a column Michael Chusid wrote nearly 20 years ago. While the use of three-ring binders has decreased as more information goes online, binders still have their place. Further, some of the concepts used to organize hard copy sales literature are transferable to your internet-based presentation.

When I send a catalog to an architect, I put it in a three-ring binder, accompanied by product data sheets and other technical information. As a cost-cutting measure, can I send the literature without a binder? And if I do use a binder, how should it be organized and presented to have maximum sales impact?—G.B., president

A sign in my dentist’s office says, “You don’t have to brush all your teeth, just the ones you want to keep.” Similarly, you don’t have to put all your literature in a three-ring binder, just the pieces you want an architect to keep.

If your primary purpose is to generate brand awareness or stimulate the recipient to make an inquiry, you can send your literature in a plain envelope or simple folder. But if you want the designer to keep the literature and refer to it in the future, then you should consider binding your materials.

Though there seems to be increasing use of paperback binding systems for building product sales literature, vinyl-clad (

Update: Consider a more environmentally sustainable material instead of vinyl) three-ring notebooks are by far the most frequently used system. They can be assembled at moderate cost in small quantities, and offer flexibility to add to or modify a presentation. They also allow designers to remove pages as required for copying, tracing (

this was important in the era of pencil-aided design), or distributing to design team members.

More importantly, notebooks address architects’ storage needs. Few architectural offices have an organized system for storing and retrieving individual brochures or product data sheets. Most loose literature pieces quickly become lost in the flood of information that flows through design offices. At best, a loose brochure may be stuck in a project file for use on a current project. But once there, it is unavailable for future reference. Binders, on the other hand, are too big to misplace in desktop clutter.

Bookshelves filled with product binders are important to the image of a design office. When prospective clients visit, the binder libraries help reassure them that the firm has the requisite technical expertise. Binders enhance your image, too; sending a binder instead of loose sheets shows you understand how architects work. It also communicates that your products have technical backup and your firm has the resources to support your relationship with designers.

Your binder gives you presence in a designer’s library. Think of it as your billboard on an architect’s shelf. While it may not have strong impact, it does have a high frequency of exposure. Every time an architect researches something in his library, or even just walks past the bookshelves, this billboard-on-a-binder exposes your brand name. Furthermore, your binder gives you visibility when the architect goes to the library to pick a product.

Building a better binder

The spine of your binder is the part most exposed to the traffic through an architect’s library, so pay special attention to its design. Most architects organize their libraries according to the MasterFormat 16-division (

there are more divisions now) indexing system, so label the spine with the appropriate MasterFormat division or five-digit (

six now) section numbers. Select an attention-getting color scheme that sets your book apart from other manufacturers in the division or section.

While your company or brand name should be on the spine, this may not be the most important text. For example, a water-repellent manufacturer with low name recognition realized that putting its company name in big letters on the spine would not motivate architects to pull the binder off the shelf. Instead, the company printed its product category prominently on the spine to appeal to specifiers trying to solve moisture problems.

Your next consideration is the binder’s front cover art. Most covers just repeat the company and brand names and product category. This may be acceptable in some instances, such as when you have to use the same binder in several market segments. But in general, you won’t get a second chance to make a first impression, so use the cover art to reinforce your product positioning or provide an overview of the product line.

For just a few cents more per piece, a binder can be fabricated with a pocket inside the front cover. The pocket is a useful place for shipping and storing samples, computer disks, catalog update sheets, and other items that don’t readily fit onto the binder rings. The pocket also encourages designers to store notes and sketches they make while studying your materials. This personalizes the binder and makes it more likely the binder will be used again.

Also, the inside front cover should have sleeves for business cards. Get two business card sleeves so you can insert a card from a local dealer or rep and a card from someone in the corporate office.

One further comment on the construction of your binder concerns recycling. To make room for new binders in their libraries, architects remove obsolete binders. Environmentally conscientious designers will attempt to reuse old binders. You can contribute to their environmental efforts by using binders with clear plastic covers and printed inserts instead of opaque vinyl with silk screened art. When the printed insert is removed (and recycled), the remaining binder is as good as new. In addition, the printed inserts allow you to use four-color art and to produce different cover art for each market segment you service.

The cover letters sent with most catalogs say little more than, “here is the catalog you asked for.” You can keep the letter brief and still recap key product benefits, explain your company’s strengths, list where your material has been used in the recipient’s community, identify your local distributors, or offer a promotional incentive. The letter is your chance to put a personal face on your company and further your relationship with the recipient.

Include a registration card or reply device, such as a postage-paid card or a fax-back survey. Use the reply device to build and update your mail list, to ask about current projects, or to get customer satisfaction feedback. If you depend on sales people or dealers to distribute your binder in their territories, code the reply devices so you can track whether your rep is actually getting the binders into circulation.

After the spine, the next most visible spot in your binder is what the recipient sees when he opens the front cover. Too often, this space is wasted on a drab table of contents or company history. Instead, bring some color and life to this page. Possibilities include your firm’s overview brochure, an ad reprint, or another piece of literature designed to build the reader’s interest, support your positioning, or explain your product line.

Finally, the key to an effective binder is a well-organized product presentation that allows a designer to find information quickly. Tabbed dividers are helpful. Some successful binders have a tab for each product line or model number (for example, residential windows, commercial windows, architectural windows). Others are organized by the type of information presented (for example, design guidelines, technical references, case studies, installation instructions, costs). Before determining how to organize your binder, review your marketing strategy and analyze the process a typical designer uses to select and specify your product.

Have a question you'd like us to answer?

Send an email to

michaelchusid@chusid.com

By Michael Chusid, Originally published in Construction Marketing Today, © 1995

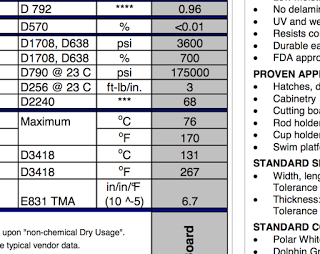

Please put a date or version number on your sales literature,

especially technical information. It will make it easier for your

customers to use the most current literature, simplify communication

between us, and help avoid conflicts due to reliance on out-of-date

information.

Please put a date or version number on your sales literature,

especially technical information. It will make it easier for your

customers to use the most current literature, simplify communication

between us, and help avoid conflicts due to reliance on out-of-date

information.