| |||

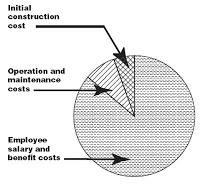

| Operational costs typically, exceed construction costs. |

The architectural community too often disregards the life-cycle costs and operation of buildings. This attitude is not expressed overtly but nonetheless permeates architectural practice:

- We grovel before a project's bid price and all but disregard a building's cash flow, the streams of operational and maintenance expenses, financing, revenue and tax consequences, which spell economic success or failure to a building owner.

- When designing an addition or renovation, we too often fail to involve the building's maintenance staff in a serious discussion about their resources, schedules, and experience with the building's existing materials and systems.

- We rarely retain qualified building maintenance consultants on our design teams.

- And frequently, we pass along a hodgepodge of submittals and call it an Operation and Maintenance Manual without considering whether the accumulation really communicates.

Building Economics

Building design and product selection decisions should be made with benefit of life-cycle cost analysis. Recently issued ASTM standards provide the building industry with clear guidelines for performing an economic analysis of building designs and components. In a life-cycle cost study, each future cash flow must be adjusted for anticipated inflation and escalation and then discounted to a present value. When performed manually, these time-consuming calculations limit the use of life-cycle cost analysis. New computer-based programs, however, make it much easier to conduct life-cycle installations.

Even though calculations have been simplified, a building life-cycle cost investigation still remains difficult because reliable data on product longevity, maintenance schedules, and operation and maintenance expenses are difficult to obtain. How soon will a roof really be repaired or replaced? How frequently will various types of door operators require servicing? How will the selection of a sealant or weatherstripping affect energy use? Such information is not contained in the typical references found in an architectural office, but a new family of facility management publications and references is beginning to fill this gap. For example, Means Facilities Maintenance Standards [now out of date] discusses the mechanisms that contribute to building deterioration, and building maintenance scheduling and management.

Architects must also take more initiative to discuss maintenance issues with their clients and consultants and to collect and analyze the maintenance history of their buildings. This information must then be transmitted to the drafters and specifiers who actually make product decisions.

Product Data

Although building product manufacturers and trade associations are a primary source of product information, few offer well documented data on their product's life-cycle performance, offering only inconclusive laboratory testing or anecdotal case studies to document their claims. They claim they are unable to predict a product's life-cycle because of conditions beyond a manufacturer's control, such as environmental conditions or maintenance procedures. Yet these variables can be quantified and applied to a sampling of historic product performance data. The resulting analysis could be used as a valid basis for predicting product performance and comparing product alternatives.

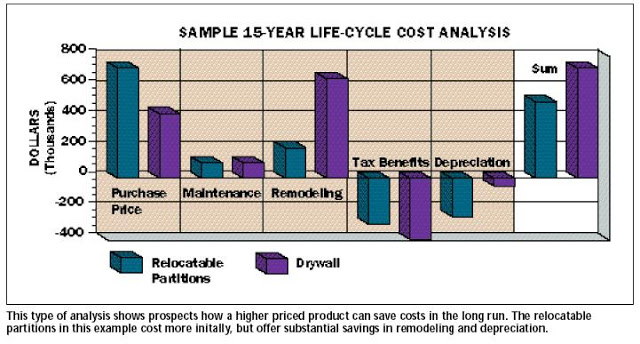

Some manufacturers have responded to the need for better information about product life-cycle costs. USG Interiors, Inc., for example, offers a computerized comparison of relocatable partitions and drywall partitions. called DesignAid for Walls, the program enables a designer to consider the economic impact of partition relocation, financing alternatives, tax benefits and accelerated depreciation, and the escalation of waste disposal costs associated with drywall partition remodeling. A similar USG DesignAid program compares several floor construction and wire distribution systems to determine life-cycle costs vis-a-vis workstation relocation. [Chusid Associates wrote both DesignAid programs.]

| |

| Building productivity is also a life cycle factor. |

Since many architects assume "building maintenance" means "janitorial services" or occasional redecorating, it would be useful to introduce a new term into our professional patois. "Operational assurance" is a concept more familiar to industrial engineers who must assure that manufacturing equipment is kept at optimum operating capacity. An operational assurance approach to buildings must consider the building operational goals and specify systems and products in view of their longevity and the ease and cost of their maintenance, repair, and replacement. Operational assurance can be applied not just to mechanical and electrical systems, but to the building envelope, finishes, and other architectural components as well.

Capability in operational assurance planning would enable an architectural or engineering firm to differentiate itself from its competitors and position itself for growth in industrial, commercial, or institutional markets. Maintenance programming, value engineering, training of the building staff, and post-occupancy evaluation also could be lucrative extended services and could lead to a continuing relationship with a client.

Have a question you'd like us to answer?

Send an email to michaelchusid@chusid.com

By Michael Chusid, Originally published in Progressive Architecture, ©1991.