This is an encore of an article Michael Chusid wrote almost twenty years ago. It is still applicable today.

My sales manager is urging me to make more architectural sales calls during the design phase. But experienced sales reps tell me I’m wasting my time if I make a call before the construction documents phase. What do they mean by project phases? And which phase is the best time to make sales calls?—J. P., sales trainee

Architects typically provide their services in a series of phases described in American Institute of Architects document B141: Owner-Architect Agreement. The sales assistance an architect needs may differ from one phase to another. Understanding the following seven phases will enable you to adjust your sales style to each.

1. The sales process begins even before a project is identified. The

pre-design phase is not just for prospecting, it provides an opportunity to form relationships with architects and their staffs and to position yourself as a valuable resource. Ask about the firm’s experience with and attitude toward your product and have the staff explain their product selection process. These kinds of questions will put you in the role of a consultant and not merely a vendor.

Architects deal with thousands of products in a typical building. The pre-design phase is not the time to overload them with data that has no immediate use. Instead, concentrate on creating positive impressions of your product’s primary benefits. Give the architect enough background to make intelligent product decisions.

In-office lunch programs are an excellent way to do this. The lunch format reaches individuals in the back office who make many product decisions but whom you can’t call on individually. Rather than fill your presentation with product facts and figures, discuss areas of broader concern. If you sell waterproofing, for example, don’t talk about application technicalities. Discuss ways to construct a building that minimizes the potential for leaks.

2. During

schematic design the architect establishes a building’s concept, size, appearance, overall quality, and budget. Decisions about major building systems may be made, such as whether a steel or concrete structure will be used. And “single line” drawings will be produced showing the building’s general layout.

Your goal at this time is not to sell your particular product, but to assure that your product type is the basis of the design. If you sell metal roofing, for example, pitch the aesthetic and functional benefits of sloped roofs compared with flat roofs. Become part of the design team by asking questions about design criteria, project schedule, and team members.

It is hard to find projects in schematic design because only a few people may be involved at this point and because many projects, particularly commercial ones, are kept quiet to give clients room to maneuver.

3. After schematic design demonstrates how the building will satisfy the owner’s needs,

design development determines how the building will be put together. The design team becomes more complex as engineers and consultants get involved. Designers will refine floor plans, size the building systems, check building code requirements, and address coordination problems.

Many products are selected at this time, especially where the selection affects the design of other systems. Some brands may be specified, but most product decisions are still generic. For example, if brick was indicated in the schematic design, the architect will now determine whether the walls are thin brick cladding, brick veneer, or load-bearing masonry. If you have already established yourself as a resource, you may be invited to help make these decisions.

4. The

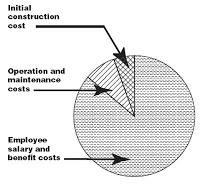

construction documents phase completes the design and preparation of detailed drawings. Products are selected by brand or performance and specifications are written. The architect expends at least 40% of his effort is during this phase, and additional staff and consultants become part of the project team.

You must be able to speak to each team member in his own language. Discuss details with the job captain, pricing with the cost estimator, warranty and delivery with the project manager, energy efficiency with the mechanical engineer, finishes with the interior designer, and product performance with the spec writer.

5. The team that worked on the construction documents begins to break up as soon as a project enters the

bidding or negotiation phase. The individuals who chose your product may be reassigned to new projects or even laid off. Just a core group remains to take questions from bidders and to prepare addenda. It is very important that these individuals understand how your product contributes to the job’s success because they are in a position to accept or reject substitutions proposed by bidders.

Bidders are now part of the design process and bring issues like pricing, delivery, and installer preference into sharp relief. I have seen salespeople struggle to get named in the specs but lose the sale because they neglected to sell the bidder. Be aware of the project’s bidding instructions regarding bid submittal, substitution procedures, and other requirements.

6. Contractors require your primary attention during

construction contract administration because they can actually write an order. But do not forget the architect. He can still accept substitutions or negotiate your product out of the job should a budget overrun occur.

The architect’s contract administrator or construction observer may not have been a part of the design team until now and may not know why your product was selected or how it is expected to perform. Try to enlist him as an ally. Tell him what to watch for in the shop drawings and on the jobsite. Remember, too, that the draftsmen who detailed your product do not have many opportunities to see construction. Arrange jobsite visits so they can see and handle your product in person.

7. A satisfied customer is your best advertisement. So use the

post-construction phase to consolidate your relationship with the architect and to lay the groundwork for future sales. Also, be sure the building owner or occupant understands how to use and maintain your product. Be responsive to complaints.

Do a six-month or one-year follow- up inspection and report your findings to the architect. Contact design team members who have lost touch with the project. They will appreciate learning about problems encountered during construction and how you helped solve them.

Take job photos and put them in your three-ring binder in the architect’s office. This will remind the staff that their firm has used the product in the past and can confidently consider it again.

As a project moves from phase to phase, the architectural personnel assigned to the project may change. Projects are often handed over with little communication or documentation about product selection decisions. You must be alert to these changes and make sure that new team members understand why your product has been considered. Be on guard, too, for fast-track construction or other scenarios that affect project phasing.

So when is the best time to make sales calls? There is no one best time. Each project phase presents sales opportunities. A useful exercise would be to analyze the types of decisions made in each phase and how they can affect your product. Get used to asking architects, “What phase of architectural service is this project in?”

It would be ideal if you could call on an architect before a project is identified and then shepherd your product through each phase. This may be practical if you can justify frequent contacts with a particular architectural firm, but most salespeople have to target more selectively.

Your strategy will depend on many factors, including your personal style, the opportunities at a particular architectural firm, and your company’s marketing plan. Some suppliers use salespeople just to answer questions or take orders. But others want them to establish stronger relationships with architects. By doing so, you can shape your prospects’ attitude towards your product and guide them through design and construction to assure a successful sale.

Have a question you'd like us to answer?

Send an email to

michaelchusid@chusid.com

By Michael Chusid, Originally published in Construction Marketing Today, ©1992